By Frank Trinh

While the country of Vietnam has gone through 'Ðổimới' ('renovation') to being a market economy and establishing diplomatic relations with America, as well as signing a trade agreement with them, the people of Vietnam have also gone through various stages, rushing and elbowing their way through to learn an international language as a means of relating meaningfully to the wider world. This has created what could be called 'English fever'.

English classes have mushroomed. It's hard to imagine how many public and private schools, and how many centres are running English training courses throughout Vietnam. People can see courses and examinations advertised everywhere. Students as well as public servants, who have been approved for overseas training, also have to improve their English, in order to get marks to reach admission levels allowing them to study at universities where English is used as the medium of instruction. Judging from the importance of English in Vietnam, one could refer to it as 'the first language' without this being considered an overstatement. Also, strictly speaking, it should be referred to as 'a second language', as would reasonably considered any other foreign language. Then what are the chances for it to become 'the third language'?

When commenting on English articles carried in various international journals by the European Economic Community (EEC) published in the 1970s, Alan Duff in his book The Third Language (1981) referred to the type of language used as 'the third language'. He cited some examples as an illustration:

In English, people do not say '*ace violinist' to describe a virtuoso violinist. They say 'top violinist'. They do not write '*indispensably necessary' to describe something which is most necessary. 'Necessary' is enough, but if it needs emphasis then they write 'absolutely necessary'. When referring to knowledge which is gained, they do not say '*knowledge is received'. They say 'knowledge is acquired'. When referring to a particular situation which has caused a division or split between some group and another, they do not say '*opened a wedge' but rather say 'caused a rift'. Even if the translator or writer wished to use the word 'wedge', in English, 'wedge' does not co-occur with 'open'. A 'wound' can 'open' but a 'wedge is driven' or 'introduced'. When talking about a wound which takes time to heal, people do not say '*the wound healed poorly and late', but 'the wound healed badly'.

The above mistakes cited were made by non-English-speaking background writers. Even though they had a sound knowledge of English, when they wrote, they thought in their mother tongue, then translated it into English. As a result, their writing does not sound natural nor idiomatic, and is not the type of English that American, Australian or for that matter English people would use in such a context. They are collocational mismatches.

The fact that English in Vietnam nowadays is looked upon as 'the third language', as viewed by Alan Duff, is borne out by the many instances of such a phenomenon. Let's consider the following:

At the entrance to a seafood restaurant named Phố Biển ('Ocean Street') in the heart of Hanoi, there was a wooden board dangling in the air and held by metal chain. On this board was a group of words, artistically carved in both Vietnamese and English. If one took careful notice, there was a Vietnamese line saying: 'Cámơn sựchọnlựa của quýkhách'. Below it was the English equivalent: 'Thank you for your choosing'. Those who have some knowledge of English know what 'choosing' means, but when they read this phrase, they should automatically ask: 'Choosing what in order to be thankful?' If someone wanted to be adamant about this they could say it was readily understood in Vietnamese, but such a phrase in English is grammatically incorrect. It is a clause lacking an object. In order to avoid this grammatical error one could write: 'Thank you for your choice', but for the purpose of using it in a correct context in English, perhaps one should write: 'Thank you for your patronage'.

At the base of the board, the phrase: 'Giờphụcvụ' was rendered into English as 'Serving time'. Grammatically speaking there is nothing wrong with this, and nothing to blame as far as word meaning goes. 'Giờ' means 'time' and 'phụcvụ' means 'serving'. The only problem is that the term 'serving time' suggests in the English-speaker's mind the time served in prison or time served in military service. In this context, people should write: 'Business hours/Hours of business', 'Trading hours', 'Opening hours', 'Operating hours', or in the case of an office, 'Office hours'. In the case of 'Serving time' at a doctor's surgery, it would be 'Surgery hours' or 'Consulting hours'.

At the bottom of the staircase of the four-star Dânchủ ('Democracy') Hotel which lies close to Hồ Gươm ('Sword Lake'), one can see, right in the middle of a green rectangular mat, an oval-shaped centrepiece, inscribed with the words in bold white print: 'Good morning'. That is to say, in the morning, before you start walking up the stairs, this greeting is there, welcoming you to the hotel. But if you were a nit-picking guest, you may ask yourself: 'How about the other times of the day, like afternoon, evening and night? Does the same greeting still apply? In order to avoid being corrected by such people, perhaps the mat bearing the greeting should say 'Welcome' to be in line with its role as 'a welcome mat'.

In Haiphong there is a four-star hotel, 8 storeys high, built about three years ago in Lạch Tray Street, adjacent to a rather large round artificial lake with an island in the middle, which is used as a Youth Activity Centre. It is not known if the hotel owner has used the name of the street, cutting it down to 'Tray' as in The 'Tray' Hotel, or if the English word 'tray' is insinuated, which means 'a flat receptacle with raised edges on which food, drinks... are served up to people'. Perhaps the term 'tray' was suggested to the hotel owner by someone, who supposedly had a good knowledge of Shakespeare and the Queen's English. The only problem is that with such a 'posh' hotel and the name 'Tray', to a native-speaker of English might it be considered a well-chosen name? Existing hotels in Vietnam, owned mostly by foreigners, have rather familiar names, such as Métropole, Hilton, Eden, Sofitel, Novotel, Omni, Rex, or New World...The word 'tray' in Vietnamese has no meaning, but when pronounced with a Northern accent, it sounds like 'chay', as in 'ăn chay', meaning 'having food without meat', or 'being a vegetarian', as when describing a Buddhist.

Also, in the hotel one can see on the walls of the lift many colourful pictures advertising the hotel's many facilities, such as the swimming pool, spa pool, massage room, conference rooms, breakfast bar, cafes, bars and restaurants and gymnasium... Below these impressive pictures there is a line saying: 'So good to enjoy, so hard to forget'. A Vietnamese with a meagre knowledge of English would be able to understand what message the hotel would like to convey which is: 'Guests will enjoy the facilities so much to the extent that they will forever remember and find them hard to forget'. The only problem is that, when asking a native-speaker of English what they would think on reading this slogan, the response may be: "We do say 'So hard to forget', but we would not say 'So good to enjoy'". It might be argued that something new can come from something old, and consequently a new catchphrase is created. A former BBC colleague of mine heard the title of a movie 'Dressed to kill', and he knowingly changed it to 'Undressed to kill'. Needless to say he caused some mirth. However, with English in a state of flux as it is at present in Vietnam, it might be best to stick to the proper and common fixed expressions. The common fixed expression in English used to describe the first situation is 'So easy to remember, so hard to forget'. In order to avoid using such an unidiomatic English slogan 'So good to enjoy, so hard to forget', but which still retains the words 'enjoy' and 'remember', perhaps native-speakers might suggest concise, compact phrases such as 'Make your stay enjoyable and memorable' or 'Have an enjoyable and memorable stay', or 'Helping to make your stay enjoyable and memorable'.

Going up to 'The Top of the Roof Free-Form Tray Pool', as stated in the Hotel brochure, instead of just 'Roof Top Swimming Pool', written on the top edge of the pool and painted in blue was the depth indicating 1.70 metres. Next to this, was a board with a sign, written in English: 'Thou shalt not dive', indicating that the depth of the pool did not preclude diving, so it was a warning not to stand on the edge at this point and dive head-first into it, unless you wanted to kill yourself. The funny thing was that the style of the warning sounded like the 11th Commandment. It's not known if the 'so-called' English-language advisor, who wrote this commandment wanted to show off his knowledge of words and their meaning, or whether he just wanted to give the guests a belly-laugh, either intentionally or unintentionally. All we know is that under normal circumstances the native speaker of English would write: 'No diving allowed'.

Patrons at The Tray Hotel have to pay US$25 for a standard room with a double bed, which includes breakfast. Every time guests go to breakfast they have to present a voucher to the reception area indicating the room number, and to verify that guests are bona-fida. If the voucher is carefully scrutinised, it states on one side, written in Vietnamese, and the other side, written in English, the types of breakfast available. The English original text states that the breakfast types are 'Buffet', 'American', 'Continental'... The Vietnamese translation, however, states that breakfast types are 'Tựchọn', 'KiểuMỹ', 'KiểuChâuÁ'. The term 'Continental' is translated as 'KiểuChâuÁ' ('Asian type'). This is possibly a case of mistaking the word 'Continental' for the word 'Oriental'. A 'Continental breakfast' is a European-type light breakfast, consisting of croissants or toasted bread, served with butter and conserves, accompanied by tea or coffee. It is different from an English breakfast, which consists of toasted bread and conserves, cooked eggs and meats or baked beans, fruit, fruit juices, and tea or coffee.

While shopping in Vietnam, you can find shops selling amenities for tourists, and for those Vietnamese with extra money to spend on the niceties of life. For instance, the buyer can pick up a neat, soft nylon-type tissue cover, decorated with colourful flowers and 'feel-good' slogans on the front such as 'Forever Love', or 'Just for Fun'... One of the slogans however was wrong and it read in English: 'Thingking for you' (verbatim) which in fact, should be 'Thinking of you' if it were correct English. On the inside of the little bag, there was the word 'Handkerchiefs' written in two words 'Handker chiefs', instead of one word. Errors of this nature can be attributed to perhaps absent-mindedness or poor English grammar and spelling.

However, the label 'Made in Hanoi', which was attached to the headgear, footwear and the likes, manufactured in the country's capital city, can be used as another example of 'the third language' in action in Vietnam.

Think about it!

Frank Trinh

Sydney, January 2002

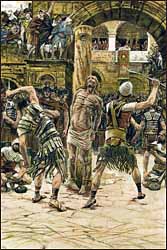

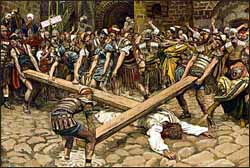

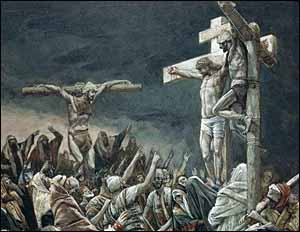

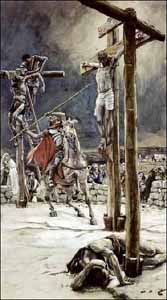

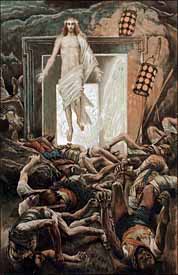

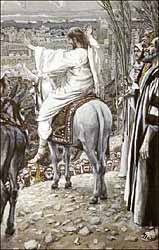

The Passion of Jesus — his notorious suffering and painful, public death by crucifixion in Jerusalem at the beginning of the Common Era — is a story Christians tell because it is a vital to what they believe. It is a story initially told by Jesus Christ, who rose from the dead.

The Passion of Jesus — his notorious suffering and painful, public death by crucifixion in Jerusalem at the beginning of the Common Era — is a story Christians tell because it is a vital to what they believe. It is a story initially told by Jesus Christ, who rose from the dead.  And so we keep his Passion in mind as an Easter story. It should not be dissected with an historian's eyes, though it is rooted in history. Rather, like the Emmaus disciples, we should look at it from the perspective of our own sorrows and questions. And as he did for them, the Risen Christ will help us reinterpret our own lives in the light of his. Immense benefits flow from this mystery: graces of rejoicing, patience and compassion.

And so we keep his Passion in mind as an Easter story. It should not be dissected with an historian's eyes, though it is rooted in history. Rather, like the Emmaus disciples, we should look at it from the perspective of our own sorrows and questions. And as he did for them, the Risen Christ will help us reinterpret our own lives in the light of his. Immense benefits flow from this mystery: graces of rejoicing, patience and compassion.